Todd Moss: When it comes to energy, big is beautiful

The soccer ball is supposed to create energy. It didn’t.

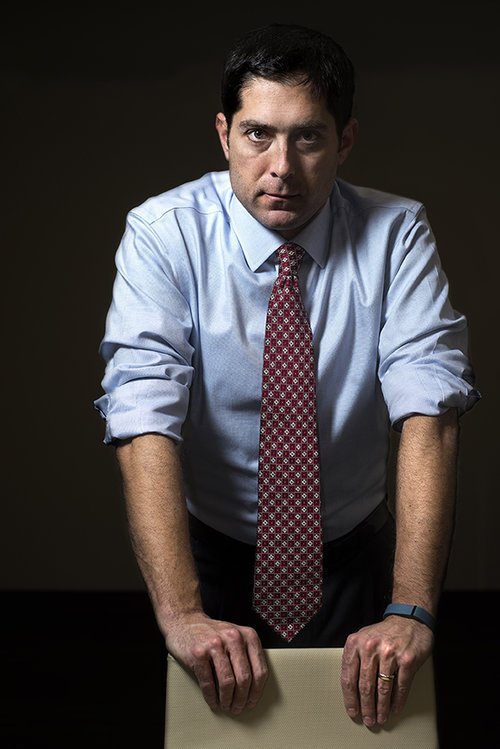

Todd Moss

Who could object to efforts to bring clean, renewable energy to people without electricity?

Donors and investors love social enterprises (D.Light, Greenlight Planet, BrightLife) and nonprofits (SolarAid, GivePower) that bring solar panels, lights or phone chargers to poor households in Africa and south Asia.

Why, even President Obama, on a visit to Tanzania, played with a Soccket, a soccer ball that generates just enough energy to power a light bulb or charge a phone.

Trouble arises, though, when these well-intentioned, small-scale initiatives draw attention away from utility-scale energy projects that can power businesses and drive economic growth--the kinds of big projects that lifted the US, Europe, Japan, China and much of the rest of the world out of poverty. Or, worse, when an absolutist devotion to renewable energy stands in the way of big, centralized projects--specifically, the natural gas, coal and nuclear power projects that, even today, provide more than 80 percent of the electricity used in the US.

This is Todd Moss’s concern. Moss, 48, is a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development, a former state department official and a PhD economist who recently launched the Energy for Growth Hub. The Energy for Growth Hub is a network of scholars and advocates who want to bring some common sense to the conversation about how get energy to everyone in Africa and Asia. They are focused not just on the 1.3bn people whose homes are without a light switch but the 3bn or so who live in places where a lack of reliable, abundant electricity remains a barrier to progress.

Moss sat down with me recently in Bethesda, MD, where we both live, to talk about how he and his colleagues want to convince policymakers to help poor countries achieve the high-energy future they need to become prosperous. Household solar panels won’t get the job done. Big wind and solar farms, natural gas plants, hydroelectric dams, geothermal plants and, perhaps, nuclear power will be required. Even if that means -- dare we say it? -- taking a small step backwards in the battle against climate change.

“Climate change is real, it’s caused by human activity and it’s likely an existential challenge to humanity,” Moss tells me. “I don’t think it can or should be solved on the back of poor Africans.”

After all, the world’s poorest people didn’t cause the climate crisis. It’s not fair to ask them to sacrifice, particularly as those of us in the west enjoy the benefits of abundant, cheap energy.

There are opportunities here for philanthropy, if only because the impacts of energy poverty are so far-reaching. Millions of people die every year because they cook over open fires. Health care clinics operate without reliable power. Schools lack electricity, Students can't study at night. Most of all, robust economic growth--the only thing that can lift large numbers of people out of poverty--requires high rates of energy consumption. Anyone who cares about global poverty should care about energy.

"A low energy future is a jobless future,” says Moss.

What's more, without industrial-scale energy, people in energy-poor places will be ill-equipped to deal with the impacts of climate change. They are the most likely to suffer from extreme heat, drought, crop failures, rising sea levels and floods. Of the 2.8 bn people living in the hottest parts of the world, only 8 percent currently have air conditioning, compared to 90 percent ownership in the US.

As Moss told me: “They’ll need more energy, not less. They need to live in resilient houses. Their roads and airports can’t be washed away by storms. They will need steel and concrete, which require lots of energy. They need to be richer.”

None of this should be controversial. It is. Some environmental groups, as well as global development agencies, are reluctant to support fossil-fuel projects or big dams, even in countries that desperately need energy and are blessed with energy resources. Opposition to large-scale hydroelectric dams, for example, has dramatically curbed support for such dams from development institutions such as the World Bank.

"Major dam projects have been cancelled or suspended in Myanmar, Thailand, Chile, and Brazil," Jacques Leslie reported at YaleE360. In an effort to halt development funding for fossil fuels, Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace and the city of Boulder, Colorado, filed a lawsuit years ago alleging that the Export-Import Bank of the United States and the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) provided financing and insurance to fossil fuel projects without assessing whether the projects contributed to global warming or impacted the U.S. environment, as they were legally required to do. And, as recently as last month, the International Energy Agency warned that the world has so many existing fossil fuel projects that it cannot afford to build any more and still achieve international climate goals. Fatih Birol, the executive director of the Paris-based group, told the Guardian: “We have no room to build anything that emits CO2 emissions.”

Really? Tell that to the millions of people who burn wood inside their homes to cook their dinner.It should go without saying that wind and solar farms should be the technology of choice to power the developing world. But it seems unlikely that they can do it alone. Battery storage remains expensive, and a sophisticated electricity grid is needed to manage intermittent sources of power. Despite rapidly falling costs, wind and solar produced just 7 percent of the world's electricity in 2015, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance. They produce even less of the energy needed for industry, transport, heating and cooling. Those percentages will grow rapidly--thank goodness--but major energy transitions take decades.

"The scale of the energy poverty problem is so great that we shouldn't ex ante take any options off the table," Moss says.

Consider Nigeria, Africa's most populous country, which is awash in natural gas. It just built a 461mw natural-gas plant, with help from OPIC, but it needs many more. With more than half the population of the United States, Nigeria can generate less than one percent as much electricity, Moss has written.

"The specter of a Nigeria that cannot come close to meeting its growing population’s demands for jobs and modern lifestyles—all underpinned by high volumes of energy—should be alarming," he says. .

The Energy for Growth Hub's network of academics intends to bring its knowledge to development institutions, as well as governments in poor countries. “We’re trying to influence decision-makers in a few capitals,” Moss says.

The organization has fellows in Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, India and a Thailand-based expert who focuses on Bangladesh. Its principal funders are the Rockefeller Foundation, the Pritzker Innovation Fund, and the Spitzer Charitable Trust.

Moss, by the way, has made things happen before from his perch at the Center for Global Development. Just this week, Devex reported on a rare bipartisan reform success in DC that took root at the think tank, in a story headlined How policy wonks, politicos and a conservative Republican remade US AID. He also has an interesting side gig as an author of political thrillers. His fourth and latest book, called The Shadow List, sends a state department crisis manager and his CIA agent wife into the heart of a corruption scandal in Nigeria. He enjoys writing novels, he told me, because writing "works a different part of your brain," although writing fiction about Washington has become harder than ever.

"Reality is too crazy," he says. That's for sure.