How FDA made a “gigantic, chaotic” mess of the vaping market

Yikes! This is my first blog post in more than six months. I’m writing less than ever (obviously) as I gradually ease into what a friend calls “rewirement.” But I can’t let go of the story of vaping and smoking, largely because the US government gets it so wrong, as does much of the coverage in the mainstream press. Meantime, the so-called public interest groups that continue to oppose safer nicotine products and demonize the tobacco industry continue to do more harm than good.

As a new administration takes over in Washington, the issue is more timely than ever. Trump & Co. have an opportunity to, quite literally, save millions of lives by fixing the FDA’s approach to e-cigarettes and other reduced-risk nicotine products. Interestingly, just before the transition in DC, FDA regulators authorized the marketing of 20 Zyn nicotine pouch products including those in flavors citrus, cinnamon, chill and cool mint. This was a welcome sign that the FDA’s Center for Tobacco Products will support the idea of tobacco harm reduction—that is, the idea that people who can’t or won’t quit smoking traditional cigarettes should be encouraged to switch to safer nicotine products, like Zyn.

If you haven’t been paying attention — or if you’ve read the often wrong-headed coverage of e-cigarettes — you may be surprised to learn that vapes and other means of delivering nicotine without burning tobacco are, first, much safer than traditional cigarettes and, second, one of the most effective, if not the most effective, way to help people who smoke give up their deadly habit.

Cigarettes kill about half of long-time smokers; e-cigarettes have yet to kill anyone, as best as we can tell. Well-regulated safer nicotine products have helped to drive down smoking rates in Japan, Norway, Sweden and the UK, among other places.

But not here — thanks in large part to the FDA. Last week, the nonprofit drug-policy website Filter published my story about the agency’s regulation of vaping under the headline “How the FDA made a “gigantic, chaotic mess of the US vapes market.” Here’s how the story begins:

Twenty-one years ago, a Chinese pharmacist named Hon Lik patented the first electronic cigarette. Lik smoked heavily, and hoped to help people quit smoking by giving them the nicotine they crave in a safer way.

His invention succeeded wildly. It spawned a $28-billion industry that is disrupting the global tobacco business. Leading tobacco control experts say that vapes have begun to reduce the disease and deaths caused by smoking, which kills about 480,000 people a year in the United States. Vaping is much less harmful than smoking, and more effective for smoking cessation than nicotine patches or gum.

Yet US regulators have made a dismal mess of the vapes market.

Instead of promoting safe and effective vaping, the federal government, led by the Center for Tobacco Products, a unit of the Food and Drug Administration, has gone to great lengths to keep vapes and other reduced-risk nicotine products out of the hands of consumers who want them.

The FDA’s unwillingness to authorize the sale of flavored vapes has created a vast, unregulated black and gray market of e-cigarettes, many imported from China. This was entirely predictable. Banning a product that people want almost never works — a lesson that regulators should have learned from Prohibition but did not.

Unfortunately, FDA was heavily influenced by congressional Democrats and anti-tobacco groups like the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids which, true to its name, focuses narrowly on protecting kids from tobacco while ignoring the needs of about 28 million American adults who smoke, Teen smoking and teen vaping are both way down, as it happens, and the Tobacco 21 law passed during the first Trump administration is expressly designed to keep tobacco products out of the hands of people under 21. But the adult smokers are being denied access to innovative nicotine products, like e-cigs, that could save their lives.

There’s much in my story for Filter. You can read it here.

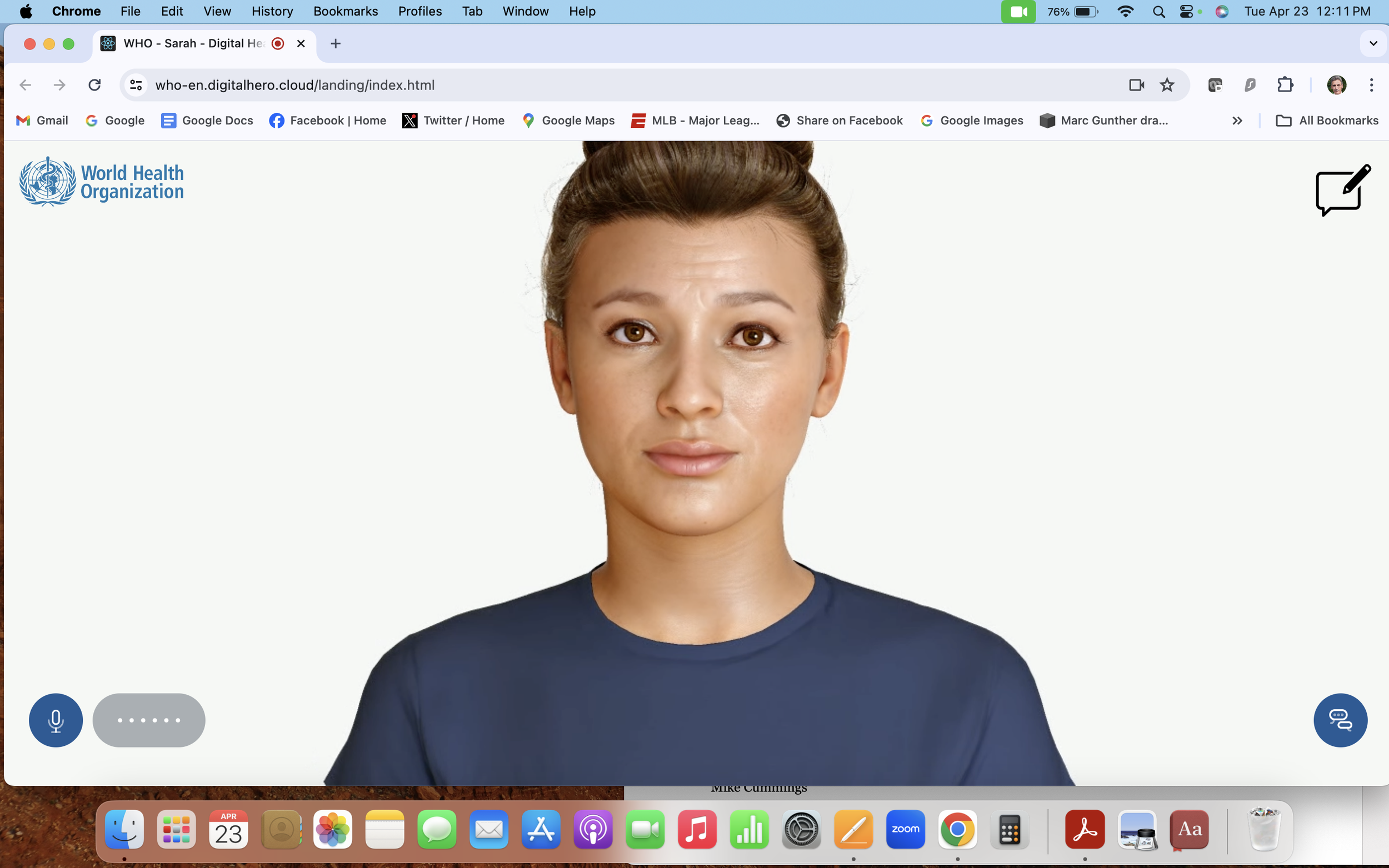

Philanthro-colonialism: Bloomberg and the WHO

Nerd alert: Here comes another story on tobacco policy. This one looks at what appears to be the undue influence of Michael Bloomberg, the billionaire former mayor of New York City, and his philanthropic arm, Bloomberg Philanthropies, on the World Health Organization.

Bloomberg, his foundation and the nonprofits they fund, including the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids, crusade against e-cigarettes, particularly those with flavors that appeal to kids. Tobacco-control experts, including most of the former presidents of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, argue for a more balanced approach—one that strives to keep e-cigarettes out of the hands of kids but makes them available to smokers who use them to quit combustible tobacco.

The WHO, as I reported the other day, is a fount of misinformation when it comes to e-cigarettes. The question is, why? Today’s story explores the influence of Bloomberg and his allies on the WHO. Bloomberg Philanthropies also spends considerable sums trying to shape tobacco and vaping policy by directly supporting nonprofits and government regulators in low and middle-income countries; this is why he’s been accused of what’s been called “philanthro-colonialism.”

Mike Cummings, a widely-respected tobacco control expert and a professor at the Medical University of South Carolina, told me:

As an important voice in public health, WHO should be basing its advocacy and communications on science, not emotion and the private view of wealthy donors. Mike Bloomberg is well respected as a champion for public health, including tobacco control, but on the issue of smoking harm reduction, he appears to be blind to the science that is emerging and the real potential to end the deadly epidemic of disease caused using smoked tobacco.

Neither the World Health Organization nor Bloomberg Philanthropies responded to my emails asking

You can read the rest of my story here at Medium.

What’s wrong with the WHO?

Lately, I’ve been writing less and enjoying life more. (Pickleball!) I’m surprised to see this is my first blog post of 2024, although that’s partly because a couple of stories that I filed with the Chronicle of Philanthropy are still awaiting publication. I’m planning to take the summer off, and then continue my graduad rift towards what a friend has decided to call “rewirement.”

Meantime, I feel compelled to return to the topic of smoking, vaping and tobacco policy. It’s so important — smoking remains the No. 1 cause of death and disease in the US — and so poorly covered by the press, when it’s covered at all, which is not often, that it’s an arena where my reporting can make a contribution. At least that’s my hope.

Today’s story is about the World Health Organization, which has a great deal of influence on low and middle income countries that look to the WHO for guidance when setting tobacco policy. The WHO opposes tobacco harm reduction — the idea that people who cannot or will not quit smoking combustible cigarettes should be permitted and even encouraging to switch entirely to safer nicotine products such as e-cigarettes, nicotine pouches like ZYN or devices like IQOS that heat but do not burn tobacco.

This is, in my view, misguided: Evidence continues to accumulate that these products are, on balance, good for public health because they enable smokers to give up combustible cigarettes and still get a nicotine fix; they’s a safer substitute for a product that kills half of its users who don’t quit. But the WHO has a perfect right to come to its own conclusions about what tobacco policies to recommend.

That said, the WHO also has an obligation to communicate honestly to governments, medical professionals and the public about the relative risks of tobacco policy. Instead, the organization misleads, putting forth half-truths that exaggerate the dangers and ignore the benefits of alternative nicotine products. That’s what my story is about, Here’s how it begins:

The World Health Organization has 8,000 employees, a budget of close to $4bn dollars, considerable influence and ambitious goals. Expanding access to medical care. Managing global health emergencies. Addressing the root causes of disease.

Even combatting misinformation online.

To the latter, one is tempted to respond, “Physician, heal thyself.”

That’s because, when it comes to one of the most important public health questions of our time — how best to reduce the death and disease caused by smoking tobacco — the WHO is not merely failing to curb misinformation. It is misleading governments, health care workers and the public.

The story goes on to cite specific, egregious examples of misinformation being spread by the WHO. It also looks at the role of Bloomberg Philanthropies in financing the WHO, the topic of a follow-up story coming soon.

Dozens of countries including China, India, Brazil and Mexico now ban the sale of e-cigarettes, according to the WHO. These countries continue to permit the sale of lethal, combustible cigarettes. That makes no sense.

You can read the rest of my story here.

Electric cars, clean energy and e-cigarettes

When big automakers turn away from polluting, gasoline-burning cars to make cleaner electric vehicles, they’re cheered.

Likewise, fossil-fuel companies are praised when invest in solar or wind power to help drive the transition to renewable energy.

Yet when tobacco companies develop safer ways to deliver nicotine–a concept known as tobacco harm reduction– they are denigrated and demonized by nonprofits that purport to care about public health.

This makes no sense.

Progress is progress, no matter who’s behind it.

But in the world of tobacco control, any action associated with a tobacco company is deemed toxic.

Consider the unfortunate story of the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World. Created in 2017 by global tobacco giant Philip Morris International, the foundation researches and supports safer alternatives to combustible cigarettes, among other things. As soon as it opened its doors, the foundation was denounced by mainstream tobacco-control groups as an industry front. Those who accepted the foundation’s money were barred from attending academic meetings or publishing in academic journals. Derek Yach, its first president, became persona non grata in the world of tobacco control.

This fall, Cliff Douglas, a lawyer and anti-tobacco activist who has spent decades battling Big Tobacco, took over as president and CEO of the foundation. As a condition of taking the job, he went to great lengths to separate the foundation from Philip Morris Internation and to refuse to accept any more industry money.

Douglas’s bona fides as an opponent of smoking are impeccable. He helped whistle-blowers expose industry secrets. He helped drive the campaign by flight attendants to ban smoking on airplanes, long before smoke-free workplaces became common. He joined in at least a half a dozen lawsuits against tobacco companies, including the case that led to the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement that transformed tobacco control. He led anti-smoking efforts at the American Cancer Society.

In a 2000 book, Civil Warriors: The Legal Siege on the Tobacco Industry, investigative reporter Dan Zegart wrote: “No single person had done more to make America hostile to tobacco than Cliff Douglas,”

But when Douglas joined the Foundation for a Smoke Free World in October, some of his former allies all but accused him of selling out.

Speaking to Reuters, Yolonda Richardson, president of the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids said that it was “ludicrous” for the foundation to claim independence after accepting a hefty payment from Philip Morris International. Deborah Arnott, chief executive of a UK health charity called Action on Smoking and Health, said the foundation was “irredeemably tainted” by the tobacco money.

In a rational world, people like Richardson and Arnott would respond to the news that Douglas was joining the foundation with curiosity, not scorn. They would take seriously the foundation’s claim that it would like to see lethal combustible cigarettes replaced by newer technologies like e-cigarettes, heat-not-burn products and oral tobacco that deliver nicotine to people without killing them. Despite the sordid history of the tobacco industry, they would be open to the possibility that the industry is changing, if only because fewer people are smoking these days, at least in the US and Europe. Tobacco companies need to develop new products to survive. [See my Medium story, Can we learn to love Big Tobacco?]

Last week, I wrote about Douglas and the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World for the Chronicle of Philanthropy. The headline: How a Debate Over Vaping Might Derail the War on Tobacco.

The story argues, among other things, that the strident opposition to vaping by nonprofits funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies is making it harder for adults who smoke conventional cigarettes to switch to vapes.

Citing the risks to kids, the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, Parents Against Vaping E-Cigarettes and Truth Initiative have led successful legislative and regulatory efforts to ban flavored vapes, which are popular with adults as well as young people.

The unintended consequences of their crusade is that more people are smoking, as the story explains:

Bans on flavored e-cigarettes, which now cover nearly 40 percent of the country, have been associated with increased sales of conventional cigarettes, according to several academic studies and financial analysts.

Douglas told me: “These bans disincentivize the far safer product and move people back to a product that’s going to kill one in two of them.”

Again, this makes no sense.

Douglas hopes to find common ground among the opponents of e-cigarettes, who argue that they are a gateway to smoking, and the advocates of harm reduction who regard them as a pathway out of smoking. The evidence favors the latter group.

There’s more in the story, including the encouraging news that smoking is way down in countries where less harmful nicotine products are available and people have access to science-based information about the relative risks of nicotine delivery systems. Sweden, Japan and the UK have all seen dramatic declines in smoking.

In the US, too, the number of people who smoke deadly cigarettes is falling — just not fast enough. It’s time to accelerate the transition to less harmful nicotine products. Lives are at stake.

Gratitude

For Thanksgiving, here are 23 things for which I’m grateful in 2023. Some are drawn from the world of philanthropy–so please read on if you are planning to make donations during the holiday season–while others are political or personal. In no particular order.

Philanthropy

Effective altruism: The brand has been tarnished, to say the least, by Sam Bankman-Fried. But the fundamental insights of the EA movement remain sound. These are people who are serious about finding the best ways to do good. If only they had more impact on the rest of philanthropy.

Give Well: Donating to GiveWell helps save lives. The organization does deep research into charities to find those that are most effective. All operate in poor countries, where the needs are greatest and your dollars go further.

Give Directly: A simple, beautiful idea: Give money to the world’s poorest people, and let them decide how to spend it. My favorite charity.

Giving Green: Which are the best nonprofits working to curb climate change? It’s a tough question to answer. The people at Giving Green have found organizations that have a big potential impact but are relatively neglected by donors.

Animal Charity Evaluators: Another meta-charity. This one recommends nonprofits, some quite small, that aim to reduce the suffering of farm animals.

Open Philanthropy: Guided by the principles of effective altruism, Open Philanthropy prioritizes causes based on three criteria: importance, neglectedness and tractability. I’ve found this framework incredibly helpful when I think where to donate, and also when I look for stories to cover as a reporter.

Arnold Ventures: Laura and John Arnold fund research and advocacy in such arenas as criminal justice, higher education and health care. Unlike many big foundations, they’re strictly non-partisan and evidence-based.

Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies: Since 1986, Rick Doblin & Co. have been working to make psychedelics safely and legally available for beneficial uses. That world is coming, slowly but surely.

Martha’s Table: I like to give locally and have long been an admirer of (and volunteer for) this Washington DC-based charity, which gave cash transfers to poor residents during the Covid pandemic.

Standing Together: I’m just learning about these Israeli and Palestinian peace activists. They say: “People don’t need to choose whether they are #freepalestine or #standwithIsrael, they need to stand with innocent people on both sides who want to live in peace and safety.”

Politics and media

Joe Biden’s big climate bill: The future of the planet will be shaped by China, which now emits more greenhouse gases than the US and EU combined, but we Americans need to do our part.

Reason magazine: Smart, libertarian takes on the folly of governments everywhere.

The Ezra Klein Show: The podcast has done great work on Israel and Palestine since October 7.

Freddie deBoer: An iconoclast and, easily, the smartest Marxist I know. He writes beautifully, too.

Andrew Sullivan: He’s been right about so many things: gay marriage, torture, Obama, Trump and the excesses of identity politics. What’s more, he’s never dull.

Matthew Yglesias: Pragmatic takes on policy and politics, with a high nerd quotient.

Personal

Adat Shalom Reconstructionist Congregation: My beloved religious community, which keeps me focused on the things that matter.

Montgomery County Road Runners Club: My running community for nearly 30 years. Yikes. We’re growing older together.

The psychedelics community: Open-minded, big-hearted people. My friend Charley Wininger says: “The best thing about the psychedelics community isn’t the psychedelics. It’s the community.”

My friends, and especially my gf: You know who you are.

My band of brothers, sisters-in-law, nieces, nephews and boyfriends: This year, 17 of us will gather for Thanksgiving dinner.

My daughters and their families: Sarah, Becca, Amy, Eric, Hudson, Sawyer, Max, Everly and Dori. My time with you brings me immense joy. I am so lucky to have you in my life.

The Rockefeller Foundation

America’s biggest foundations wield power. They deserve scrutiny, which is why I like to report on what they do and how they do it.

And yet. These billion-dollar institutions are so lacking in accountability that it’s not clear to me that critical journalism about foundations can make a difference. So I wonder whether it’s worth my time and trouble to write about their work.

This month, the Chronicle of Philanthropy published a pair of stories that I wrote about the Rockefeller Foundation, which held an endowment of nearly $8 billion at the end of 2021. No Apologies: Rajiv Shah Stands Behind Rockefeller’s Top-Down Approach looks at the foundation’s strategy, which cuts against the grain of much of today’s liberal philanthropy. Rockefeller loves grand initiatives and relies heavily on experts, holding onto power for itself and asking the nonprofits that it funds to carry out its goals.

For what it’s worth, this strategic top-down approach, when done right, can be effective. Rockefeller’s history demonstrates that; it helped develop the yellow-fever vaccine and drove the Green Revolution. I’m an admirer of Open Philanthropy, Arnold Ventures and the Gates Foundation, all of which favor a top-down approach.

The alternative is the philanthropy of MacKenzie Scott, who has donated more than $14 billion to about 1,600 nonprofits, with no-strings attached, to “use as they see fit,” she says. The Ford Foundation, with its BUILD program, also shares power as well as money with the nonprofits it supports.

My second Chronicle story, headlined Rockefeller’s Rajiv Shah: Highest Paid CEO Among Big Foundations, asks why Shah is paid nearly $1.7 million a year. That’s substantially more than any other leader of a major foundation, although at least a dozen foundations including Gates, Ford, Lilly, Hewlett and Packard have bigger endowments and give away more money than does Rockefeller. Shah’s track record at Rockefeller has been spotty, with some wins and some losses, but he appears to have the full support of his board of trustees. He has been good to them—earlier this year, the trustees and their spouses were all invited to a board retreat at the Bellagio Center, a meeting place on the shore of Lake Como in Italy that is owned by Rockefeller. Nice work if you can get it.

Medium subsequently published my commentary under the headline, Raj Shah’s $1.7 million salary is a bit much. (The Chronicle stories are paywalled; this one is not.) Among other things, it reports on a previously-undisclosed complaint against Richard Parsons, the former CEO of Time Warner and board chair of Citigroup, who as chair of the Rockefeller Foundation was accused of having an improper relationship with a young, female staff member. The foundation investigated, as it should have, hiring the New York law firm of Paul Weiss to look into the matter, at a cost of $1.7 million. But it never disclosed the complaint against Parsons and will say almost nothing about the results of the investigation; that’s as good an example of any of the foundation’s lack of accountability.

Now Rockefeller is putting its marketing muscle behind Shah’s new book, Big Bets. The foundation is even paying for a video billboard in Times Square. Proceeds from book sales flow back to Rockefeller but surely there are better ways to spend the foundation’s money. It’s all too easy, alas, for the board and staff to spend money with no one keeping watch on what they do.

Reporting on foundations is challenging. They are very slow to publish their tax returns, which list their contributions, and they have no obligation to explain how they spend money on their own operations and administration. Rockefeller spent about $1 on itself for every $3.17 it pushed out the door in 2021, more on a percentage basis than any other big foundation, partly because it relies heavily on its staff and consultants to do the work that other donors farm out to nonprofits.

The other difficulty in reporting on foundations is that most people who know anything about them are reluctant to talk. They are either funded by their foundation grants, or would like to be. The culture of philanthropy is terribly polite.

I hope my reporting on Rockefeller gets the attention of its trustees. I can’t say I’m optimistic. There’s no scandal at the foundation, just a lot of money flowing around in ways that don’t do as much good as it should. So I will continue to wonder whether my time and effort is better spent elsewhere.

How Yale researchers helped create the ketamine industry

The clinical trial that set the stage for today’s fast-growing ketamine industry runs just three pages long and involved only eight patients. It was published, not in the New England Journal of Medicine or The Lancet, but in a specialized journal called Biological Psychiatry.

Psychiatrists at the Yale School of Medicine did the research. They were seeking to understand the basic biology of depression, and in particular the role of glutamate, a chemical that carries electrical impulses in the brain. Knowing that ketamine, an anesthetic, triggers glutamate production, they gave ketamine to patients with major depression.

To the amazement of the researchers and the patients, patients given ketamine felt better right away. The study, titled Antidepressant Effects of Ketamine in Depressed Patients, was published in 2000.

Nothing much happened, for a time.

—-

That’s the opening of my latest story for Medium. It grew out of an encounter with Dr. John Krystal, the chair of the department of psychiatry at Yale Medical School and perhaps the world’s leading expert on ketamine. Ketamine has been around as an anesthetic since the 1970s; it was used on the battlefield of Vietnam.

I heard Dr. Krystal, a careful and soft-spoken scientist, speak at the Psychedelic Science 2023 conference in Denver in June, and followed up with a phone interview. With his colleagues at the Yale school of medicine, Dr. Krystal discovered its anti-depressant qualities by accident. Their research laid the groundwork for today’s sprawling and largely unregulated ketamine industry. It’s remarkable to me how little we know today about ketamine—although there’s no doubt that it has brought relief to thousands of people suffering from depression.

Dr. Krystal is also the co-founder of a startup that aims to improve the durability of ketamine treatments, which would have the effect of lowering their costs and improving safety. You can read the full story here.

Truth or (unintended) consequences

When Ocean City, MD, banned smoking and vaping from its boardwalk, the city manager said visitors to the popular seaside resort would police themselves.

“Will we haul people off to jail for smoking on the boardwalk?” asked David Recor. “No, that’s not our approach.”

It hasn’t worked out that way.

This month, Denzel Elam Ruff, a 34-year-old tourist, defied an order from police to stop vaping. He was surrounded by three policemen, pushed to the ground and punched by one of the officers, cell phone footage shows.

Ruff, who is Black, was charged with disorderly conduct, resisting arrest, second-degree assault, and failure to provide proof of identification, all misdemeanors.

This wasn’t the first time that Ocean City police used force against vapers. In 2021, police tackled, tasered and arrested four Black teenagers after a confrontation over vaping on the boardwalk.

Ethan Nadelmann, the former president of the Drug Policy Alliance, noted on Twitter:

Anyone who thinks that banning #vapes, flavored #ecigs or #menthol #cigarettes is not going to replicate what we’ve seen with #marijuana #prohibition, ie, #police arresting lots of young people, especially boys and men of color, well, think again!

These violent confrontations should be kept in mind in the wake of a new report from Truth Initiative, the US’s largest anti-smoking group, that calls for bold and sweeping government actions to gradually end the use of all tobacco products — not just cigarettes, which are lethal, but safer nicotine delivery systems as well.

The report, called Gamechanger, says restrictions on the sales of cigarettes and vapes “must focus on the products themselves and policies should be written so that the violators are the manufacturers and retailers, not people who use, possess, or purchase tobacco or nicotine products.”

During a webinar about the report, Robin Koval, Truth Initiative’s president and CEO, scoffed at the idea that a ban on all tobacco products would lead to over-policing, dismissing it as “really a distraction.”

This is naive at best naive and disingenuous at worst.

To its credit, Truth Initiative would like to phase any ban on tobacco products, to give today’s smokers more help in quitting and more time to do so. One of its policies would prohibitthe sale of tobacco products to people born after a certain date, creating what’s been called a “Tobacco-Free Generation.” The upscale Boston suburb of Brookline, MA, for example, has banned tobacco sales to anyone born after January 1, 2000. A similar law passed in New Zealand takes effect in 2025. These laws recognize that today’s smokers struggle to quit.

But Truth also wants an immediate ban on all flavored tobacco products, including e-cigarettes, which millions of former smokers have used to help them quit cigarettes. Truth is also urging the FDA to immediately ban all menthol cigarettes.

Consider, for a moment, the unintended consequences of such actions.

Does Robin Koval really believe that police would ignore people selling menthol cigarettes on the streets, if they become illegal?

Has she forgotten Eric Garner, who was choked to death by a New York City police officer while being arrested for selling loose cigarettes without tax stamps?

Has Truth paid any attention to history?

In the epilogue to Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition, author Dan Okrent’s deeply-researched history, he writes:

In almost every respect imaginable, Prohibition was a failure. It encouraged criminality and institutionalized hypocrisy. It deprived the government of revenue, stripped the gears of the political system, and imposed profound limitations on individual rights. It fostered a culture of bribery, blackmail and official corruption.

The 50-year-old war on drugs isn’t going well either. In 2021, the CDC for Disease counted more than 107,600 drug-related deaths — an all-time high.

Now Truth wants to launch a war on nicotine that is all but doomed to fail.

Remember, there are more than 1 billion smokers around the world.

“Can anyone name any psychoactive substance enjoyed by many which has been more-or-less eradicated from planet earth in the last few thousand years?” asks Alex Wodak, a physician and the director of the Australian Tobacco Harm Reduction Association.

There’s lots more to say about Truth’s Gamechanger report. I wrote about the report last week in Filter, and wrote a longer critique of Truth Initiative last year, also in Filter.

Truth, the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids and Bloomberg Philanthropies have spent so much time and money on their crusade against vaping that it’s easy to forget that there’s been some excellent news about smoking lately.

The smoking rate in the US fell to a historic low last year even as e-cigarette use is rising, according to the CDC.

This isn’t accidental, of course. People in the US and around the world are switching from lethal cigarettes to safer ways to obtain nicotine, including vaping.

The terrible irony is that the misguided crusade against vaping will keep more people smoking, cause more death and disease and, astoundingly, benefit the tobacco industry.

Unintended consequences, indeed.

A dispatch from Psychedelic Science 2023

Historic is a word much overused in journalism, so we’ll leave it to others to say whether Psychedelic Science 2023 will be long remembered. But the gathering staged last week in Denver by the nonprofit Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Science (MAPS) certainly felt momentous: It showcased the size, strength and diversity of the fast-growing movement to bring psychedelics into mainstream America.

Some 12,000 people — 12,000 people! — converged on the Colorado Convention Center. They were scientists, physicians, therapists, activists, investors, entrepreneurs, philanthropists and, yes, psychonauts who toured an exhibit hall where vendors sold books, T-shirts and grow-kits allowing anyone to propagate psilocybin mushrooms at home. They endured long days of panels and PowerPoints and enjoyed long nights of partying and partaking in mind-altering chemicals.

The conference offered plenty of serious conversation but a playful and mildly subversive vibe was never far from the surface. Carl Hart, a drug-reform activist, a heroine user and tenured professor of psychology at Columbia, warned that he might not be his best self as he took the stage for a 9:45 a.m. interview. “I don’t usually see the day before noon,” he noted.

Support for psychedelics came from politicians, notably Jared Polis, Colorado’s Democratic governor and Rick Perry, the former Texas governor, a Republican. Other bold-faced names — NFL all-star quarterback Aaron Rodgers, singer Melissa Etheridge and best-selling author Andrew Weil — testified to the benefits of these mind-expanding drugs.

Others described the many paths by which psychedelics are becoming more available to more people in more places than ever. Plans for so-called psychedelic service centers in Oregon and Colorado, whose voters have decriminalized plant medicines, are well underway; before long, anyone over 21 in those states will be able to experience the magic of psilocybin mushrooms, in a regulated environment.

Elsewhere, a growing number of churches provide psychedelics as sacraments; they’re protected, more or less, by laws guaranteeing religious liberty. Underground markets appear to be flourishing, and retreat centers are springing up in Jamaica and Costa Rica. Nonprofit groups like the Heroic Hearts Project take combat veterans to Costa Rica or Peru for treatments.

Perhaps most important, MAPS’s drug-development unit, called the MAPS Public Benefit Corporation, expects to get FDA approval next year for its plan to treat PTSD with a combination of therapy and MDMA, or ecstasy.

It’s no wonder that MAPS founder and president Rick Doblin relished the scene as conferees packed into the 5,000-seat Bellco Theatre for the event’s opening plenary.

“I can only wonder, am I tripping?” asked Doblin. Pause. “It’s not that I’m tripping, the culture is tipping.”

With more than 500 sessions, the conference sprawled every which way. Sample titles: “90 Years of Tryptamine Chemistry.” “Can modern psychedelic medicine take lessons from the plant medicine traditions?” “Assessing the evidence for microdosing.” “Decolonization and the psychedelic renaissance.”

Not surprisingly, “Sex, Money, Death and Psychedelics” drew a standing room only crowd.

Lucid News provided extensive coverage, with reports here.. Below, I’ve pulled excerpts from my contributions and added a few observations.

—

You can read the rest of this story at Medium.

The collapse of Field Trip Health

It’s an exciting time for psychedelics. Clinical trials using psychedelics to treat PTSD, addiction, depression and anxiety are proceeding apace. Oregon and Colorado are preparing to regulate psilocybin-assisted therapy. Cities are decriminalizing so-called natural medicines, and the state of Kentucky, of all places, recently decided to spend $42m to research the healing potential of ibogaine, a naturally occurring hallucinogen found in a West African shrub. Yes, Kentucky. And Texas.

This month, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) expects to welcome as many as 10,000 people to Denver, aka the Mile High City, for Psychedelic Science 23, the biggest gathering ever of the psychedelics industry.

All that’s missing is the industry.

Startup companies seeking to develop psychedelic medicines are struggling to raise money, and a few high-profile companies have filed for bankruptcy or been forced into mergers.

Last week, Lucid News published my story about Field Trip Health, a publicly-traded company that burned through $100m of investor money and is now being sold off in pieces. Here’s how the story begins:

Welcome to the era of psychedelic stocks,” declared Forbes.

It was October 2020. A startup called Field Trip Health had just gone public on the Canadian Securities Exchange. The birth of a psychedelics industry was upon us, some said.

These molecules “stand poised to fundamentally revolutionize how we consider mental, emotional and behavioral health,” said Ronan Levy, the co-founder and president of Field Trip.

He may well be right.

But Field Trip Health, a high-profile upscale chain of ketamine clinics that burned through nearly CA$100 million in investor money before collapsing in March, won’t be leading the way.

Instead, Field Trip’s story is a cautionary tale. Developing the potential of FDA-approved psychedelic medicines will require time, vast sums of patient capital and the support of regulators, government payors and private insurers so that psychedelic-assisted therapies can be fit into the existing health-care system in the U.S.

By most accounts, Field Trip’s ketamine-assisted therapy brought relief to patients, some of whom had exhausted all other options. That’s encouraging news.

But psychedelic-assisted therapy, for now, lacks a business model. How to bring its benefits to people who are suffering will be a major topic at Psychedelic Science 23. I’m looking forward to learning more in Denver.

You can read the rest of my story about Field Trip Health here at Lucid News.

Philanthropy, capitalism and racial justice

This week, The Chronicle of Philanthropy published two long stories (here and here) about foundations, nonprofits and racial justice. Reporters Alex Daniels, Sono Motoyama and I talked to about 45 people, trying to better understand how foundations and nonprofits responded to the so-called racial reckoning set off by the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers in 2020.

To the degree that a consensus emerged, it was an unsurprising one: We were told by leaders of nonprofits that foundations have made progress, but not enough progress, when it comes to supporting the cause of racial justice. This is entirely predictable because advocates who focus on a specific issue –racial justice, climate change, human rights, disaster relief, failing schools, or homelessness–always say that funders should be doing more.

Another theme that emerged was a bit more surprising: Some of the richest and most influential liberal foundations, including Ford, MacArthur, Hewlett, Packard and Open Society, are increasingly giving up power as well as money. They are giving no-strings-attached, multi-year grants to Black-led organizations that engage in grass-roots organizing to build Black power. It has become conventional wisdom in lefty philanthropy that this is the way to improve the lives of Black Americans. Color me skeptical.

Finally, it became clear that, as with so much else in philanthropy, no one can be sure which strategies and programs to promote racial justice are working and which are not. The practice of evaluation itself is being challenged by insiders in the field, who argue that traditional notions like objectivity and rigor get in the way of racial equity. Color me even more skeptical.

Put simply, vast sums of money are flowing from rich foundations to grass-roots groups to accomplish vaguely-defined goals, with little accountability. The lack of knowledge about what works and what does not should matter more than it does.

The argument for giving unrestricted money to community groups is sometimes summed up by saying that the people closest to a problem are those closest to a solution. It’s almost become a cliche.

Marginalized people deserve to be heard, of course. “Nothing about us without us,” a phrase popularized by the disability-rights community, is an important principle. It means that no policy should be decided without the full participation of those who will be affected. That’s a matter of effectiveness as well as justice.

But trusting community groups alone to solve problems caused by centuries of racism in employment, housing and education makes no sense. Expertise matters. If my computer is on the fritz, I get tech help. When a pipe bursts, I call a plumber. If I were to get cancer, I’d see an oncologist.

Solving social problems, too, requires expertise. Does requiring body cameras curb police abuses? Do gun buybacks curb violence? What’s the effect of rent control on housing affordability? What’s the best way to teach kids to read? How does family structure affect upward mobility?

Scholars have studied such questions for decades. Grant-makers and community activists who want to improve the well-being of Black Americans should, at the very least, become familiar with their work.

Consider, for example, that capitalism, for all its problems, has helped lift billions of people out of poverty, making possible a world that is wealthier, healthier and better educated. The world’s happiest countries — Finland, Denmark, Iceland, Israel, The Netherlands, Sweden, Norway, Switzerland, etc — all enjoy market economies, along with progressive taxes and a strong safety net.

Yet foundations run by smart people fund the Movement for Black Lives, which aside from its accountability issues, wants to abolish market economies along with the police and prisons. “We are anti-capitalist,” the movement says. So are Cuba and Venezuela; they’re not faring very well.

Liberal grant-makers are not anti-capitalist but they generously fund nonprofits that advocate for bigger government, higher taxes, a stronger safety net and more regulation. My June 2022 story for the Chronicle, Can Philanthropy Remake Capitalism?, reports on the work of the Ford, Hewlett and Omidyar foundations to develop alternatives to neoliberalism.

Fortunately, institutional philanthropy is not monolithic. Corporate and conservative grant-makers say that unfettered capitalism is not the problem but the solution to the racial wealth and income gaps. They want to make it easier for Black Americans to start businesses and own their own homes.

You can read the rest of this story on Medium

Why I invested in Tactogen

Psychedelic medicines are generating excitement everywhere — among academic researchers and therapists, in the press, even with members of Congress — everywhere, that is, but among investors. Several startups developing psychedelic therapies have gone bust. Shares in others sell for less than the price of a latte. Companies developing psychedelics struggle to raise capital.

So it was with trepidation that I recently invested in Tactogen, a startup that is developing synthetic molecules to complement or replace MDMA.

Why, you ask? Because MDMA is an extraordinary drug and Tactogen wants to make it better. Let me explain.

MDMA — chemical name, 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine — is better known as ecstasy, molly or, going back a ways, as the love drug. Love drug says it best: MDMA brings out feelings of empathy, connection and trust. Developed by Merck in 1912 and then forgotten, it was rediscovered by the brilliant, renegade chemist Alexander “Sasha” Shulgin at his Lafayette, CA, lab in 1976.

Shulgin loved MDMA. “I feel absolutely clean inside, and there is nothing but pure euphoria,” he wrote in his lab notes. “I have never felt so great, or believed this to be possible. The cleanliness, clarity, and marvelous feeling of solid inner strength continued throughout the rest of the day and evening. I am overcome by the profundity of the experience.”

This was quite the testimonial, coming, as it did, from a man who invented and sampled a mind-boggling array of drugs in his lifetime.

Can we learn to love Big Tobacco?

This week, the UK government made a startling announcement about electronic cigarettes — startling, at least, to those who have absorbed the barrage of anti-vaping messaging here in the US.

The Brits said they would hand out free vaping starter kits to about 1 million people who smoke. The UK health ministry will also pay pregnant women to quit smoking cigarettes and switch to vapes.

These policies are driven by science. The evidence that vaping is much safer than smoking is overwhelming. What’s more, electronic cigarettes, along with other new-generation products that deliver nicotine without burning tobacco, help smokers to quit. They have potential life-saving benefits.

Yet here in the US, elected officials, the FDA, CDC and anti-tobacco groups have together managed to ban or restrict the sales of e-cigarettes, especially flavored vapes, while lethal combustible cigarettes remain widely available.

The thing is, the markets for these alternative nicotine products are increasingly driven by Philip Morris International, Altria and British American Tobacco, parent company of R.J. Reynolds–the global cigarette makers often derided as Big Tobacco.

In a story at Medium, I take an in-depth look at the tobacco companies and their embrace of what’s called tobacco harm reduction — the idea that people who smoke but are unable or unwilling to quit should be offered safer ways to obtain a nicotine fix.

This is an important and mostly untold story. Here’s a link.

In the story, I argue that it’s time to rethink our attitudes towards the tobacco companies:

Neither the industry’s ignoble history nor its continued dependence on cigarettes justify efforts to block Big Tobacco’s efforts to sell less harmful products that could reduce the death and disease from smoking…The companies have shown with their deeds as well as their words that they want to persuade people to buy safer nicotine products

There’s lots more to say about this, and I invite you to read my story here.

A turnabout for MAPS

Several years ago, an investor offered to pay $150 million for 20 percent of MAPS public benefit corporation, the for-profit drug-development subsidiary of MAPS, according to Rick Doblin, the nonprofit’s founder and president. MAPS — it stands for the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies — has for nearly 40 years been working to bring psychedelic medicines to the mainstream. It is thought to be tantalizingly close to winning FDA approval for MDMA-assisted therapy to treat people with PTSD.

Doblin turned down the investor. He told Lucid News that the valuation was too low, and that MAPS would sell equity in its drug-development unit “only as a last resort.”

It’s last resort time.

This week, reporting for Lucid News, I broke the story that MAPS has hired Cowen & Co., a New York investment bank, to sell shares in MAPS PBC, as the wholly-owned drug development unit is known. MAPS PBC estimates that it will need to spend somewhere between $70 million and $250 million to commercialize MDMA-assisted therapy, assuming the treatment protocol is approved by the FDA.

So far at least, MAPS has been unable to raise that money through philanthropy. Since Doblin founded MAPS in 1986, it has raised a total of about $140 million in donations. Through the first nine months of last year, it raised less than $10 million in donations.

Can Doblin raise the money, from some combination of investors and donors? The stakes are high, not just for MAPS and for those suffering from PTSD who could benefit from the treatment, but for the entire psychedelics sector.

Although MDMA is not a classic psychedelic, it is classified as a Schedule 1 drug by the DEA, meaning that it has no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. Getting FDA approval for a combination of talk therapy and MDMA mean that the medicine has been shown, through rigorous clinical trials, to provide medical benefits. Getting insurers to cover the treatment would further reinforce the idea that MDMA, which is known on the street as ecstasy, has value to patients. Finally, a successful rollout of MDMA to treat PTSD could bring enormous relief to millions of people, including combat veterans and victims of sexual assault or abuse, who suffer from PTSD. It would show that at least one psychedelic medicine can deliver on its promise.

As Daniel Goldberg, a founder of the venture capital fund Palo Santo, told me for my story: “It’s incredibly important to the entire sector and to the movement in general that MDMA gets across the finish line.”

MAPS PBC is exploring a variety of way to raise money for commercialization, an executive there told me after my story ran. Investors are definitely interested, this executive said. The question is, what will they want in return—seats on the board, influence on the speed and scope of the rollout, a focus on short-term profits?

It’s also possible that a super-rich philanthropist could pay for the rollout, on his own or with a few wealthy friends. The Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation has been one of MAPS’ most generous donors, giving the organization $3.4 million, largely to support its work with veterans. The billionaire owner of the New York Mets could write a check for 50 times that amount, and hardly miss it.

Goldberg, for one, is optimistic that Doblin will successfully finish the work to which he has devoted much of his adult life. “If anyone can do it, MAPS, and particularly Rick, will find a way to get it done,” he said. Let’s hope he’s right.

You can read my story about MAPS here.

Treating cancer patients with psychedelics

Most of you, I’m sure, have friends or relatives whose lives have been upended by cancer. Oncologists are better than ever at treating cancer; death rates from common cancers, including lung, breast, and prostate cancers have declined steadily for years. But they are not as well-equipped to deal with the emotional suffering – the depression, anxiety or fear of death – that often accompany a cancer diagnosis.

A startup company called Sunstone Therapies, which operates out of the Aquilino Cancer Center in Rockville, MD, has set out to change that. Sunstone provides cancer patients and, in some cases, their family members with therapy assisted by psychedelic medicines, including psilocybin, MDMA and LSD. Preliminary findings from a small trial of 30 cancer patients who were administered psilocybin and therapy are very encouraging.

The stories emerging from the trial are powerful, too. Here’s Pradeep Bansal, a Long Island, NY, gastroenterologist with metastatic cancer who participated in the Sunstone trial, speaking on a podcast.

"I don't think anybody can truly describe the [psilocybin] experience. One can use phrases and words that are common - ineffable, mystical, powerful. All I can say is it was the most powerful experience of my life that I have gone through, ever."

I visited Sunstone’s new offices to research a story about the company for Lucid News. Sunstone is noteworthy because some of its clinical trials treat patients in groups; this reduces the costs of psychedelic therapy and it may well help participants better integrate their psychedelic trips because they share the experience with others. The founders of Sunstone include two experiences oncologists, Manish Agrawal and Paul Thambi, and Bill Richards, an elder of the psychedelic movement who treated patients with LSD and psilocybin during the late 1960s and early 1970s, before authorities stopped research into psychedelics for about 25 years, as part of the War on Drugs.

I came away impressed by the people I met at Sunstone. Their work is profoundly important. You can read more in my story for Lucid News.

Welcome to my new blog

Welcome to my new blog. Here you’ll find my writing about the business, science, politics, culture and history of psychedelics. I can assure you that there’s lots to write about.

Yesterday, for example, I went to an event on Capitol Hill organized by the Psychedelic Medicine Coalition, a new Washington DC-based advocacy group whose mission is to “create, protect, and promote safe, equitable access to psychedelic medicines.”

That’s pretty much my mission, too. I’m interested in writing about other things – tobacco control issues, philanthropy, animal rights – but the psychedelic renaissance unfolding now is the most important and interesting story that I want to tell.

I’ve been reporting on psychedelics since 2019, when I wrote a long story for The Chronicle of Philanthropy about donors who supported research into psychedelic medicines during the decades when neither the government nor private companies would do so. Like many, my interest in psychedelics was sparked by Michael Pollan’s excellent book, How to Change Your Mind. What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence.

While researching that story, I met Roland Griffiths, a pioneering researcher at Johns Hopkins University, who pointed me to studies showing that classic psychedelics, particularly psilocybin, show great promise in treating depression, anxiety and addictions. What’s more, he said, the benefits of the treatment lasted months or years. “It’s unprecedented in psychiatry that a single, discrete intervention can produce durable effects,” Griffiths told me.

That got my attention. So did the research into psychedelics emerging from other leading universities including NYU and Yale, my alma mater. One fascinating finding: Psychedelics appear to be “trans-diagnostic,” that is, able to treat an array of mental ailments, which suggests that they work by changing deeply-rooted patterns in the brain. Over time, I’ve also heard numerous people describe how psychedelics, often in combination with therapy, helped them alleviate suffering they had lived with for years. Some took these compounds in FDA-approved clinical trials. Others did so in underground settings.

My reporting convinced me that psychedelics can be life-changing.

This does not mean they are a panacea. They are not for everyone. They are not risk-free. They must be respected. These are powerful medicines.

But they are coming, down one path or another. Medicalization as the FDA approves MDMA and psilocybin as prescription medicines, probably in the next two or three years. Through decriminalization as cities and states, including Oregon and Colorado, make them available at regulated healing centers. Or at plant-medicine churches that offer psychedelics to all comers.

So much about all this remains unknown, which is why it’s a great topic for journalism.

Gilgamesh is all about drug discovery

Many startup companies developing psychedelic medicines are struggling to raise money these days. Not Gilgamesh Pharmaceuticals. Founded in 2019, Gilgamesh raised $39m in December. Its original investors came back for the Series B round. It participated in the Y Combinator accelerator for startups. Its founder, Jonathan Sporn, who I met briefly at a party during the Horizons conference in New York, has an impressive resume. So I decided to take a closer look.

Lucid News posted my story about Gilgamesh the other day. What’s noteworthy about the company is that it isn’t developing any of the classic psychedelic drugs as medicines. Psilocybin, mescaline, LSD and ketamine have great promise as medicines, when accompanied by talk therapy., but they are all in the public domain. They can’t be patented. Perhaps more importantly, they can almost surely be improved. They can be modified to become safer, or more effective, or longer acting, or shorter acting, or easier to administer.

So Gilgamesh is developing new drugs, and building an intellectual property portfolio that will continue to attract investment, if all goes well. These novel medicines, the company says, will harness the potential of psychedelics to revolutionize the treatment of mental illness. The process is expensive and time-consuming. Chances are, Gilgamesh will need at least seven years before any of its new drugs are commercialized and available to people with depression or addictions. But if its drugs outperform the classic psychedelics, they will be worth the wait.

Here’s a link to my story about Gilgamesh.

Roland Griffiths and his legacy

Late in 2018, while researching a story about philanthropy and psychedelic medicine for the Chronicle of Philanthropy, I drove up to Baltimore to visit Roland Griffiths, a professor in the departments of psychiatry and neuroscience at Johns Hopkins. Griffiths was then and remains today one of the world’s leading researchers of psychedelics. Our conversation was one of a number that helped persuade me to make a late-in-life course change: I shifted the focus of my reporting from philanthropy to the business, politics, culture and science of psychedelics. Psychedelics is the most exciting story I’ve covered since the rise of the Internet.

Griffiths, I’m certain, has changed the lives of many others–students, researchers, the philanthropists who kept research into psychedelics alive when neither corporate nor government funding was available. In a story that I just published to Medium, I make the claim that he’s done more than anyone to bring about the mainstreaming of psychedelics.

His long career is now winding down. He’s 76, and has Stage IV colon cancer. The cancer has responded well to treatment.

But, instead of fading quietly into the background, Griffiths is sharing the experience of facing death and seeking to establish a program at Johns Hopkins that will carry on his explorations of psychedelics, spirituality and well-being.

He says: “Unlikely as it may seem, my wife and I have experienced my diagnosis as a gift, a blessing, really, Today, I’m more awake, alive and grateful than I have ever been before.”

You can read my story about Roland Griffith at Medium by clicking here.

My charitable giving in 2022

Since I began reporting on foundations and nonprofits back in 2015, I’ve tried to make a habit of writing once a year about my own charitable giving.

I’ve done so for three reasons. First, I believe in transparency. If I write a story about GiveDirectly, say, readers should know that I’m also a donor. Second, I think it would be helpful if more people shared their giving practices. We might all get smarter about where to give and, perhaps, choose to give more. Third, I have the modest hope that–as someone who has paid careful attention to philanthropy and reported on many charities–my giving might influence others.

Charities to which I donated in 2022 include GiveWell, GiveDirectly, Animal Charity Evaluators, Martha’s Table, Adat Shalom Reconstructionist Congregation, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Science and the brand-new Roland Griffiths Fund.

I explain my thinking in this post at Medium.

The smearing of a tobacco scientist

The website Tobacco Tactics calls itself “the essential source for rigorous research on the tobacco industry.” Operating under the aegis of the University of Bath in the UK, Tobacco Tactics is funded by, among others, Bloomberg Philanthropies, the philanthropic vehicle of billionaire Michael Bloomberg. Bloomberg leads a global campaign against the tobacco industry and all its products, including safer nicotine products.

Last month, Tobacco Tactics went after a Norwegian researcher named Karl Erik Lund, alleging that he has “ties” and “connections” to the tobacco industry. This was shameful. Lund has testified against the industry in five lawsuits, and has never taken any money from tobacco companies. His sin, such as it is, is that he has researched the effects of a safer non-combustable nicotine product known as snus, which are popular in Norway and Sweden. Snus, which are oral pouches, create health risks but they are safer than combustible cigarettes; they have helped reduce the prevalence of smoking and smoking-related diseases in both countries. As a result of this unfair attack, Lund was informed by a French government agency that he could no longer attend a conference on e-cigarettes in Paris that he had helped to organize.

I wrote about this at length for Medium [click here] for a couple of reasons. First, the ban on Lund was outrageous and unjust. Second, because it reflects the utter refusal of Bloomberg Philanthropies and its allies to consider ideas that diverge from its absolutist stance against all things tobacco.

To my delight, the story got a lot of attention, including a tweet that directed me to a disclaimer on the Tobacco Tactic website:

Although we work to rigorous standards and adhere to a strict guide to writing, there is no undertaking by either TobaccoTactics.org or the University of Bath that any part of this site is accurate, complete or up to date. You use this site at your own risk, and for guidance only.

Crazy, no? A university-run website calls itself an “essential source” but adds a disclaimer saying, essentially, that the site cannot be trusted to be accurate. There’s a lot more to this story, which can be found here.