Alex Hershaft: An animal rights pioneer, with a #metoo problem

AH

Yet another prominent animal rights activist is being accused of treating women badly. This time, the spotlight is trained on Alex Hershaft, an 83-year-old Holocaust survivor, the founder of a pioneering farm-animal protection group and the organizer of the animal rights movement’s oldest and most important conference.

Andrea Jacobson and Cara Frye, who formerly worked for Hershaft, are urging him to cede control of the Animal Rights National Conference, which he has run for more than 35 years. Others--women and men--agree.

“If you want what is best for the movement,” Frye wrote on Hershaft’s Facebook page, “step down from your position of power over the Animal Rights Conference. We need a diverse team of activists co-chairing the conference before it can become a safer, more inclusive meeting space.”

“Should Alex step down as conference chair? Yes, of course,” says pattrice jones, a longtime animal rights activist who has clashed with Hershaft.

She says: “We need a national conference at which every sector of the movement is represented, where attendees actively confer with each other rather than passively listening to movement “stars” pontificate, where everyone has the chance to hear the newest and most innovative ideas while assessing the success (or lack thereof) of ongoing efforts, and where everybody can focus on doing that important work without worrying about being groped or otherwise harassed.”

Hershaft told me that he’s made mistakes but that he is neither sexist nor abusive towards women. His accusers, he said, have an ax to grind. But he also disclosed that he is planning to turn the AR conference over to his longtime associate, Jen Riley, who can lead it, “with my help of course.”

By email, he said: “I dread for the future of our movement, until this hatred and anger calm down.”

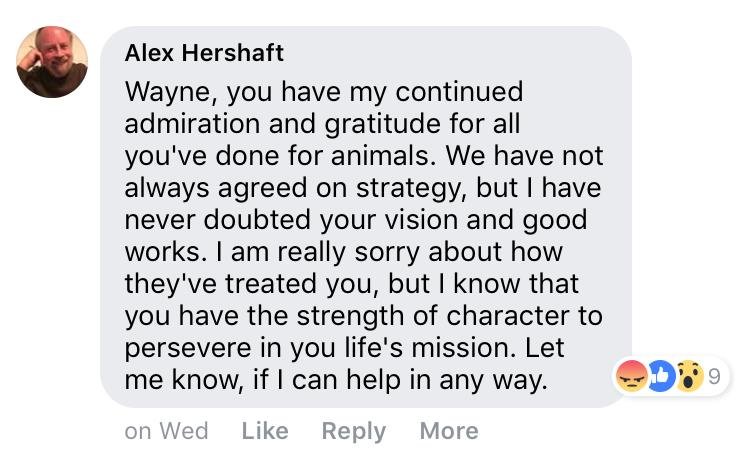

The thing is, Hershaft has no one to blame but himself for his current troubles. He set off a firestorm when he posted a comment on Wayne Pacelle’s Facebook page supporting the former chief executive of the Humane Society of the US, who resigned on Feb. 2 amid allegations of sexual harassment:Women were enraged, and said so.

Hershaft then deleted his praise of Pacelle, along with the critical reactions, and then did his best to apologize, without mentioning Pacelle. This, again, was met with derision. Hershaft subsequently deleted the apology as well. But it was too late. Frye and Jacobson came forward to describe what they experienced as an abusive workplace at FARM (Farm Animal Rights Movement), the small nonprofit led for many years by Hershaft. Others said that women and people of color were relegated to secondary roles at the annual animal rights conference, and that Hershaft was slow to respond to reports of sexual harassment at the event.

The campaign against Hershaft follows successful efforts led by women to shame Pacelle, Paul Shapiro, formerly of the Humane Society and Nick Cooney, formerly of Mercy for Animals, over allegations of sexual harassment. All have denied the charges, for the most part. All are out of the movement for now.

Hershaft is right about one thing: Some women in the movement are angry. Emboldened by this #metoo moment, some are speaking out for the first time about mistreatment that they have experienced or witnessed for years. More broadly, they are voicing long-simmering frustration about what they see as an injustice: The fact that a relatively small number of men have held power in the movement and take credit for its success, while women did most of the work. Making matters worse, it turns out, is a history of abuse in the movement: A former Humane Society of the US executive named David Wills was sued for sexual harassment and fired by HSUS way back in 1995. Last year, Wills was charged in a Texas federal court with sexually assaulting a nine-year-old girl.The allegations against Hershaft do not rise to that level of heinous behavior, thank goodness. Mostly he stands accused of being sexist, insensitive, and abusive (a word that means different things to different people) and of leering at women.

What women are saying

Here’s a sampling of the allegations, from Facebook and in follow-up interviews with Nonprofit Chronicles.

Stephanie Bain, a west coast animal welfare activist, said to Hershaft on FB:

I was helping run the Animal Place table at AR2016 where we had a human-sized battery cage on site. We invited you to step inside the cage and you made sexually suggestive comments about getting into the cage with me and two of my female co-workers. Women activists shouldn’t have to be subjected to overt sexualization by the organizer of the national animal rights conference.

Cara Frye, who worked at FARM for five years, said Hershaft occasionally insisted that staff members work at the FARM office--which was located in his Bethesda, Maryland, home--until well past midnight. “Going to the office to work late at night was uncomfortable,” she said.

Several staff members said Hershaft has a habit of staring at women’s breasts. This is evidently an old habit: A book called Girls to the Front, about the DC women’s punk rock movement, quotes a woman who in 1991 worked part-time “at the Farm Animal Reform Movement, whose director was an old guy who wouldn’t stop staring at her breasts.”

Another longtime FARM employee said: “He would watch porn on his computer. If I were working past 7 or 8 p.m., I’d hear moaning and spanking sounds.” One staff member stumbled across signage from sex parties held in his home.

Andrea Jacobson, who spent nearly three years at FARM, said she was discomfited when Hershaft asked to hold her hands after a meeting. She recalled that, during evenings at the AR conference, which features a lively bar scene, she would see her boss “pin women against the wall and kiss them.” Whether these encounters were consensual or not, she couldn’t say, but they set the wrong tone, she said.

Some of the most compelling evidence against Hershaft comes from pattrice jones, the co-founder of VINE Sanctuary, an animal sanctuary in Vermont. In an email, jones told me that women and people of color have repeatedly asked Hershaft to put more women onto the plenary stage, but they have been rebuffed. When women organized their own discussion circles at the event, Hershaft chastised them. Later, jones said, FARM began “more or less openly requiring organizations to pay money for their people to be given plenary slots. Of course, this created a cycle where the better-funded organizations became more and more well-known, helping them to raise more and more funds.”

In a private Facebook post called The Shape of the Movement that jones shared with me, she vividly describes a banquet speech at the AR2002 event by Howard Lyman, a cattle rancher who became an animal rights activist. Lyman, she said, ogled women as they left the stage, prompting activists to protest after the banquet ended. Lyman refused to apologize, as did Hershaft, who subsequently banned some of the protestors from the conference. Their differences were later resolved by a mediator. It’s a troubling story that you can read, in full, here.

Carol Adams, whose 1990 book, The Sexual Politics of Meat, explored the relationship of patriarchal values and meat eating, told me:

It is very hard for some male leaders in the animal rights movement to stop valorizing other male leaders in the movement. The annual conference participated in this valorizing over the years. Many of us fought for a policy on sexual harassment for the conference. Back in the early 21st century, when the conference organization was structured in such a way that Alex was the one who had to agree to any policy, he finally agreed to a policy on sexual harassment, but he picked the ombudsman to whom any experiences be reported—and it was a man. He was standing next to me before he went up to announce the new policy at a plenary session, and when he came back, he said, “I hope you are satisfied,” as though it was about me and not about responding to an issue of safety and justice.

As for the conference program, there’s a perception among women that Hershaft favored men with coveted speaking opportunities. Activist lauren Ornelas, the founder and executive director of the Food Empowerment Project, told me: “I could certainly vouch for the fact that most of my talks were relegated to small rooms and I have felt the boys club has gotten the biggest promotion.”

Progress has been made in diversifying the speaker lineup. By my count, 12 men and 10 women were given speaking slots in plenary sessions last year. Of the 159 people who spoke, 72 were women. (Hershaft said that about 60 percent of the speakers were women, if you include moderators.) Women account for 75 or 80 percent of those who work in the animal protection movement, it’s been estimated.

Hershaft: Some regrets

What does Hershaft say about all this?

He told me that he regrets praising Pacelle in public, but did so as a gesture of friendship. “It was done inartfully, leading to misinterpretation,” he said. Bain and Jacobson, he said, misunderstood his intent in the incidents they described. (Jacobson was fired from FARM, he noted.) If women kissed him at the conference, he said, there was nothing inappropriate about it.

“I’m sort of a folk hero,” he said. “A lot of women come up to me and hug me and want to have their pictures taken with me.”

As for the criticism from pattrice jones, Hershaft said he wishes he had handled it differently. Jones can be confrontational and she “feels like it is her mission in life to bash men,” he said, but she deserved a respectful hearing. “That was an excellent teaching moment,” Hershaft said. “I wish I had taken advantage of it.”

He also disputes the notion that men dominate the movement’s leadership. He sent me a list of 15 leading animal rights groups, and said that 10 of them -- PETA, Compassion Over Killing, Animal Equality, A Well-Fed World, VegFund, United Poultry Concern, Friends of Animals, In Defense of Animals, International Primate Protection League and the Anti-Fur Society -- are led by women. He has turned most of the programs run by FARM, his nonprofit, over to Compassion Over Killing, which is led by Erica Meier.

Hershaft also referred me to Shemirah Brachah, who has worked with him for about 12 years. "He can be difficult to work for," she said, because of his strong opinions. But he is "very soft spoken, never seems to lose his temper and has never been inappropriate" in her presence.

These days, though, women in the animal protection movement expect more out of men. They want allies. Last summer, in a sign that the AR conference has become open to feminist views, Carol Adams delivered a presentation titled The Second Class Status and Exploitation of Women in the Animal Rights Movement: Ten Questions.

In her talk, Adams asked: “When will we have an ethical commitment to women’s equality in the animal rights movement?”That, it appears, is what women are insisting upon now--and not a moment too soon.Update: As this blog was about to be published, I heard from Dawn Moncrief, a board member of FARM, about plans for the conference. She said by email: "An advisory committee is being created so that decision-making is more diverse and has more institutionalized checks-and-balances. Tangible changes in the conference schedule and priorities are also planned in response to (and to amplify) the positive call for increased gender and racial equity within the conference and the movement. While these are very difficult and emotionally-charged times, my hope and expectation is that these are growing pains that will result in long overdue change and a more socially just, inclusive, and cooperative model for leadership and advocacy."

***Credit where credit is due: Two blogposts helped shape my thinking about women in the animal protection movement. This one is by pattrice jones, this one by lauren Ornelas. Carol J. Adams blog has a wealth of insights, and here’s a story about why Saying You’re Sorry Isn’t Enough Anymore.